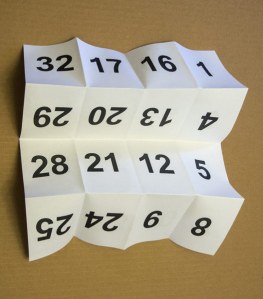

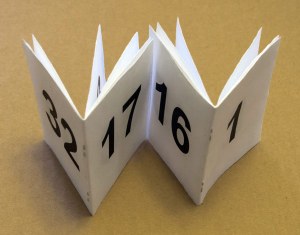

Most picture book writers and illustrators learn pretty quickly that a standard picture book is thirty-two pages long. But why? True, that is a convenient length –- not too long, not too short. And some books are twenty-four pages long, or forty-eight or sixty-four, but usually the number goes up or down by multiples of eight or sixteen pages. Yes, there’s a practical plan afoot.

Books do not quite pop out of some machine like Dr. Seuss’s from The Sneetches, which puts instant stars on your belly. That would be cool. But still, the process seems magical. Books are printed as press sheets, then trimmed and bound. It’s the layout of that press sheet that affects the number of pages.

It was once common for the illustrator to go to the printing company when the book was printed. Imagine seeing a stack of ten thousand press sheets for your book! The one pictured here, for Giants of Smaller Worlds, actually has the entire 48 pages laid out on one side of the sheet for proofing purposes. Normally there would be 24 pages on each side, which is how the pages are printed for the book.

Each of the rectangular areas on the sheet is one page. Notice that there are no blank pages. That would waste paper. Also some pages face one way, some the other. And look at the giant dragonfly. It is a Meganeura, a prehistoric organism with a 29-inch wingspan. Since all of the giant insects in the book are drawn actual size, this one spanned four pages. (We’re glad there are no more Meganeuras today!) But the parts of the dragonfly art are not next to one another in the press sheet. How do they get together in the finished book? Follow the pictures.

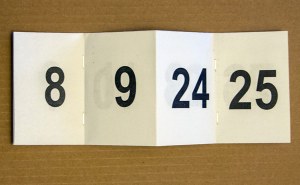

A sliver of paper is trimmed from top and bottom to free up the pages. This explains why any art that goes to the edges of the page must extend an extra 1/8”, since it will be trimmed. Now the “press sheet” is two signatures of sixteen sequential pages each, with none loose. The Meganeura appears in sequence, too.

Ah, but what if your story does not fit conveniently into a format that is a multiple of sixteen? The pages can be arranged on a different sized sheet, however money is saved if everything can be standard. A common solution is to manipulate the content–to make sure the whole story fits in the pages that are available, during the dummy stage.

The printer’s page count begins on the very first page of the signature and ends on the thirty-second. That first page is often the title page. Page two is for copyright/dedication. This is the “front matter,” and page three is where the story begins. Sometimes more pages are used up front, for example when there is a “half title page” on page one, a double page title spread on pages two and three, the copyright on page four with dedication on five, and the story beginning on six or seven.

Another solution that uses up more pages of the signatures is called “self ends.” The clue to self ends is whether the book has decorated or plain endpapers.

This book has endpapers that are of a solid color and are in fact of a different, heavier paper than the interior. These pages are glued in and are not part of the press sheet. Page one of the press sheet is the title page and page thirty-two is the last page of the story. The endpapers are a separate design element.

Here, where endpapers are decorated, page one and page thirty-two are glued to the covers, and therefore not visible. Pages two, three, and four are considered endpapers and the same happens at the back of the book. Now the book’s actual content is only twenty-four pages long! Tricky, eh?

So, the press sheets go from printer to bindery and magic happens. Voila! A bound book.

Photos by Egils Zarins

Related posts on Writers’ Rumpus:

Finally Seeing the F&G by Paul Czajak

The Alphabet Soup of Publishing by Jen Malone

3 Ways to Pace Your Picture Book by Joyce Audy Zarins

Related post on Writing for Kids (While Raising Them):

Picture Book Construction: Know Your Layout by Tara Lazar

Fascinating peek into the process. Thanks, Joyce!

LikeLike

It was wonderful for PB illustrators and author-illustrators to be able to see the entire process all the way to the printed press sheets. Perhaps the pendulum will swing back that way again. The South China Printing Company and other Asian printers were doing most PBs for many years. Tough for illustrators to travel that far for a press run!

LikeLike

Great visual explanation of why a PB is 32 pages!

LikeLike

Thanks, Tara. I try. I’ve done demos of this at schools and even teachers are often surprised.

LikeLike

This is very interesting! I am not a children’s book writer/illustrator, but, as the mother of three young children, I am a heavy consumer of picture books. I had noticed that they were around the same length, but I never really thought about why that might be (except to think it might be related to children’s attention spans–and parent’s patience around bedtime!).

LikeLike

Hi A.M.B. You are of course also right about how attention spans and patience have an influence on story length. But of course there is that other practical matter of economics in production. Here is another insight. If you look at old picture books, many don’t seem so colorful. That’s because they were printed using ony two or three colors to save money. A regular “full color” book actually is printed only in four colors – magenta, cyan, yellow and black. Different percentages layered one on top of the other give us the “full” color we see every day.

LikeLike