By Danna Zeiger

Novels-in-verse hold a special place in my heart. As an emotional person, and one who loves poetry and playing with words, verse has a way of digging deep into my core in the best ways possible.

And Marcella Pixley’s Neshama did not fail to deliver. I cried, I shrieked, I gasped. I devoured the entire book in one sitting on a quiet Shabbat and I could. Not. Put. It. Down.

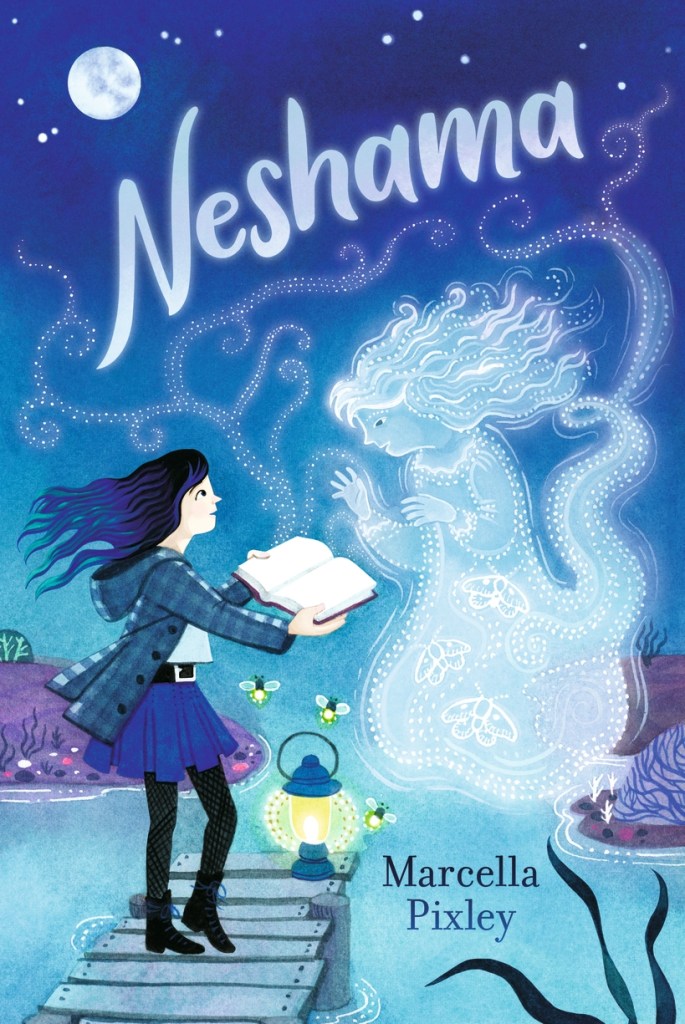

No kidding. I settled into the couch, warm and cozy, and picked up this book with the beautiful ghostly blue cover… and the next thing I knew, I was blinking away the last tears, looking up in confusion as the world around me re-emerged, and the clock magically jumped a few hours closer to Shabbat’s end.

Lucky me! For the book that has haunted me, I had the opportunity to process and mold some of the questions nagging at me: both about the book and these ethereal characters who felt the most real, as well as of the incredible author and her witchy writing powers that captivated me. As I write this post, months in advance of its release, I can already see the multiple award nominations, and with great reason! I think all of us writers can learn from Marcella! Let’s dive in…

DZ: Where did you get the idea for this book? There are so many unique facets to this book: the ability to see and hear ghosts, the young Ruthie who died young, the antisemitism, the fraught relationship between Anna and her parents, Anna’s pull towards Judaism in a nuclear family that has pulled away. Which of these were personal or based on real life? Where did you come up with these ideas? Tell me at least Bubbe is based on a real-life bubbe! I loved her!

MP: My books are always part truth and part fiction. Many aspects of NESHAMA come from my own life. Ever since I was a very little girl, I have had vivid dreams in which deceased loved ones have come to me with messages for family members and friends. Most of the time they just want me to pass on a message of love, forgiveness, and assurance that they are okay. Other times they want me to pass on that they are still “watching” and connected to those they left behind. I have always wondered if the dreams were real visitations or just my writing-mind making up stories, but I treat them as though they might be real and always pass along the message just in case. I got the idea for NESHAMA standing on the porch of our ancient summer cabin in Gloucester, MA and wondering how many spirits might be standing there with me. I am so glad you love Bubbe. I do too! She is based on my mother, Jackie Fleischman, who is an incredible mother to me and bubbe to my children. She has wild white hair, and she makes the best chicken soup on earth.

DZ: Did you research Jewish perspectives on any of these facets for this book? For example, is there a Jewish perspective to ghosts or the afterlife of souls? All I really know about is the practice of saying kaddish to elevate the soul!

MP: Yes, I did. I wanted to make sure this book was accurate as well as poetic, so I did research all through the writing process. I also met with my Rabbi and asked him to be a sensitivity reader to make sure everything I wrote was as accurate as possible from a Jewish perspective. I learned that while there isn’t really an idea of ghosts in Jewish religious practice, there is the idea that each of us has a neshama, a divine spirit or spark inside of each of us that can never be extinguished. Our neshama continues to exist in the universe even when our bodies die.

In Yiddish folk tradition, however, there are centuries of stories and superstitions that have to do with ghosts. There are even different names for different kinds of ghosts depending on their origins and intentions, including the dybbuk, the golem, and the ibbur, which is the type of ghost that Anna meets in NESHAMA. Unlike a dybbuk or a golem, an ibbur is the ghost of a righteous soul who asks permission to enter the body of a living person so they can complete a task they were unable to finish. The living person exists for a time with two separate souls living inside them. It is a very strange concept, but perfect for my novel, and I hope, perfectly spooky for my readers.

DZ: I love Gloucester, MA–do you have a personal connection there?

MP: Oh, yes. Gloucester is my soul-place. When I was growing up, my parents had an old, wooden summer cabin that I have always been certain was haunted. You can feel the spirits as you walk around on the porch or down by the dock. The most haunted time of day is right before sunset when the light slants in at the windows, casting a dusty reddish glow, and you can see the shadows against the walls all stretched out with the dust glimmering. I have always felt generations of people wandering through these shadows. I wrote the first draft of many of these poems in Gloucester, waiting for the ghosts of that place to speak to me.

DZ: Did you ever consider making this a YA book, considering some of the spooky/creepy elements? Or did you feel like you were closing a gap in MG, specifically? How do you make these kinds of decisions, or is it just about what feels more natural for the story?

MP: Although I have written YA, I have a particular fondness for middle grade books and for the middle grade author community. I also have a fondness for the years between 9-13 when a child is right on the threshold of adolescence and their soul is fierce and wild. Most of my books have an element of make-believe and imaginativeness in them which seems to make most sense with a pre-teen protagonist. I think middle grade books can afford to be quieter and more lyric than YA. Even though there are spooky elements in NESHAMA, I think it is perfect for ages 9 and up. At its core, it is really a story about love, forgiveness, redemption, and bravery.

DZ: You’ve written both prose and verse novels. How did you decide to make this one verse? Did you try it in prose? How did your writing process change when working on a verse novel?

MP: My first published work was poetry. In graduate school, I studied contemplative poets like James Wright, Mary Oliver, William Stafford, and Philip Levine, and I became fascinated with how a person can look so closely at something ordinary that it can become extraordinary. The poetry I wrote in my twenties always contained a turn, an epiphany, a moment towards the end of the poem when suddenly the speaker makes a discovery. This is the moment that my dear professor Arthur Smith called ex-stasis, the moment where our spirit soars. My novels have always had a lyric element in their prose style, but I missed the poetic form. When I started playing with NESHAMA, I knew it had to be a novel in verse, but I didn’t want to just write broken prose lines. I wanted these poems to behave like the poems I studied in graduate school. I wanted each one to contain a moment of discovery. NESHAMA began as an experiment in writing poetry with the dead.

The hardest and most interesting thing about writing a verse novel for me was learning that sometimes action has to happen in the blank spaces between poems or stanzas. These are spaces that would contain exposition, dialogue or detail in a prose novel. With a novel in verse, the reader fills in the blank spaces with their own imagination. In this way, the reader takes part in the creation of the story. The most wonderful thing about writing NESHAMA was re-discovering that moment of discovery where the speaker looks so deeply at her world, where she can become so observant of the place or the object or the wind or the spider web or the eyes of the ancestor that for just a moment, she makes a discovery that can change her, and if we are lucky, it can change us as well.

DZ: I love the back story about Jeremy, his abusive father, and the antisemitism Ruthie experienced. You must have written this story long before October 7, 2023, right? Antisemitism was certainly alive before then, but not quite as prevalent in the world. What made you want to write this storyline, and how has your perspective on it changed since antisemitism has exploded in the last year and a half?

MP: Oh dear, such a hard question. Yes, I began writing this book in 2021 and as you say, antisemitism has erupted in a very visible, immediate and heartbreaking way since then. In NESHAMA, Ruthie is teased and tormented by Jeremy, a neighbor boy with a troubled past. Ruthie’s family is the only Jewish family on their street. I chose to explore Jeremy’s traumatic home-life, not to excuse his behavior toward Ruthie, but to help create three dimensionality in a key character who otherwise would have become another kind of stereotype. Jeremy’s mistrust and ultimately his lack of empathy towards Ruthie comes from his own experience with abuse and neglect as a child as well as his own ignorance. I wanted to allow a path for redemption where the adult Jeremy could reflect on his own behavior and to ask forgiveness. If we do not learn to forgive, we can not heal.

I struggled with how to keep Jeremy accountable for his actions but also show the possibility of growth, redemption and forgiveness. I wondered if I should close the door on Jeremy and simply allow the other characters (and the reader) to hate him for his prejudice, but it felt important to recognize that every person has a story, even those who hurt us, and listening deeply to that story can be an act of courage. All humans are deeply flawed. In this world, where perspectives tend to be black or white, it is very hard to accept that we live in a world filled with nuance and uncertainty. Sometimes the best we can do is ask questions. Is it possible to condemn a person’s actions but still see them as a three-dimensional person who has suffered their own wounds? Can we feel anger and also empathy at the same time? How do we hold space for our own dignity and also insist upon the dignity of others? These have always been important questions for me and they have become even more important since October 2023.

DZ: How did you write this book? Did you plot it out or use traditional craft books like Save the Cat? Do you have a novel-in-verse writing group, or did you edit heavily? Did you play with order of poems or make major shifts? With a novel-in-verse, these writing changes can be more difficult to consistently apply throughout, right? Do you think it’s harder or easier, and how in general does it compare to working on prose novels?

MP: I am not a person who plots in advance. Generally, I begin with a question. When I started NESHAMA, my question was “What would happen if a little girl was able to see the ghosts of her ancestors? What would they say to her?” Then I started bringing a journal down to the dock in Gloucester, and I imagined that my ancestors and I were writing poems back and forth to each other like lyric postcards. I would ask a question and I would imagine how they would answer. I allowed them to tell me all about what they missed about being alive. I pretended that they were yearning for contact and sensation. I pretended that they were hungry. They missed sitting at our tables. They missed lighting shabbos candles and sipping sweet wine and tasting the salty tears of chicken soup. All of the poems written by the ancestors in NESHAMA came from those experiments.

The real magic happened in the drafting process. I did a great deal of shuffling, deleting, and reordering. I spent almost a year following specific arcs of the story through the entire manuscript and making certain that they developed in a satisfying way, growing within and between the poems as Anna made discoveries about herself, her family, and her world. Because each poem played the part of a chapter in prose, those changes were often tiny and involved finding the right word, the right image, the right nuanced line that would extend a single plot point or develop a character. It was like putting together a wonderful puzzle.

DZ: You’re a middle school teacher, so I’m wondering what you see in the classroom. Middle Grade sales are down, and we’re told that verse novels are harder to sell… have you noticed a change in what your classroom kids read? Do they gravitate towards shorter books? Or away from verse?

MP: My kids LOVE novels in verse. My classroom library is stocked with them and the kids gravitate to them all year long. We read Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson to discuss ideas of identity and self-expression. Then eighth graders begin choosing more novels in verse as mentor texts to help them write poetry about their own complex identities. There are so many gorgeous books in my classroom library written by verse novelists that my students and I admire including Lisa Fipps, Chris Baron, Elizabeth Acevedo, Margarita Engle, KA Holt, Jason Reynolds, Kwame Alexander, Aida Salazar, Thanhha Lai, and so many others. They become our teachers. We make space for them to sit beside us as we write.

DZ: So many Jewish books are published by Jewish imprints, and they are stunning and lovely. Was it hard to gain interest from a non-Jewish publisher, and was your framing and pitch focused on the Jewish content? I’m curious especially as a Jewish author, after chatting with many Jewish authors in NCTE of 2024 and hearing that so many are struggling to get Jewish stories published these days, as well as the many articles that say the same.

I have been very lucky to find a home for many of my books at Candlewick Press. My editors Liz Bicknell and Ainslie Campbell are wise, compassionate readers and wonderful human beings who are committed to publishing diverse voices and perspectives. When I began sending drafts of this book to Liz Bicknell back in 2022, she encouraged me to explore Jewish identity and to look even more deeply into the topic of antisemitism. She was less interested in “what sells right now” and more interested in finding brave and beautiful stories that matter by diverse voices. Not only is Candlewick publishing NESHAMA in May 2025, but in September of 2026, they will be publishing my first picture book ONCE UPON A SUNRISE, which is a story based on my grandfather’s immigration from Divin, Poland to Brooklyn, New York and a very special soup pot that contains the wishes and tears of three different generations.

DZ: What is your advice for burgeoning MG or YA writers? Any favorite classes/workshops/books that you would recommend?

MP: My best advice is to not pay too much attention to what you think sells, or what you think the current trends say. What is most important is to write the story that is in your heart. Express all the strange parts of who you are. Write about the parts of you that hurt the most, the parts of you that don’t fit into the mainstream, the parts of you that clash and struggle and sigh and rage – those are the stories that need to be told. And if one of your identities is on the margins in this world, well then let it step onto center stage. These are the brave parts of you that most need to be shared. Writing is an act of courage. Your story will help someone silent realize they are not alone.

*GIVEAWAY*

Marcella is generously offering both a critique and an AMA with this interview!

She is also happy to donate cheerleading and support to any author who wants to be in touch with her.

TO ENTER: please comment on this blog post. If you share on Instagram, Bluesky, or Facebook, you get another entry–just add to your comment to share both your handle (e.g. @SOMEAUTHOR) and where you’ve shared it. Please state which prize you would like.

We will select winners at random. Giveaway closes in one week.

More about Marcella:

Marcella Pixley is the award winning author of five novels for young people. Her recent middle grade novel, Trowbridge Road, was long listed for the National Book Award. It was a Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection, and it was a finalist in the Massachusetts Book Award and the Golden Dome Award. Marcella teaches Language Arts in Carlisle Massachusetts. She lives in a haunted house with a shaggy dog named Mango.

Information and Purchase Link for Neshama

20 comments