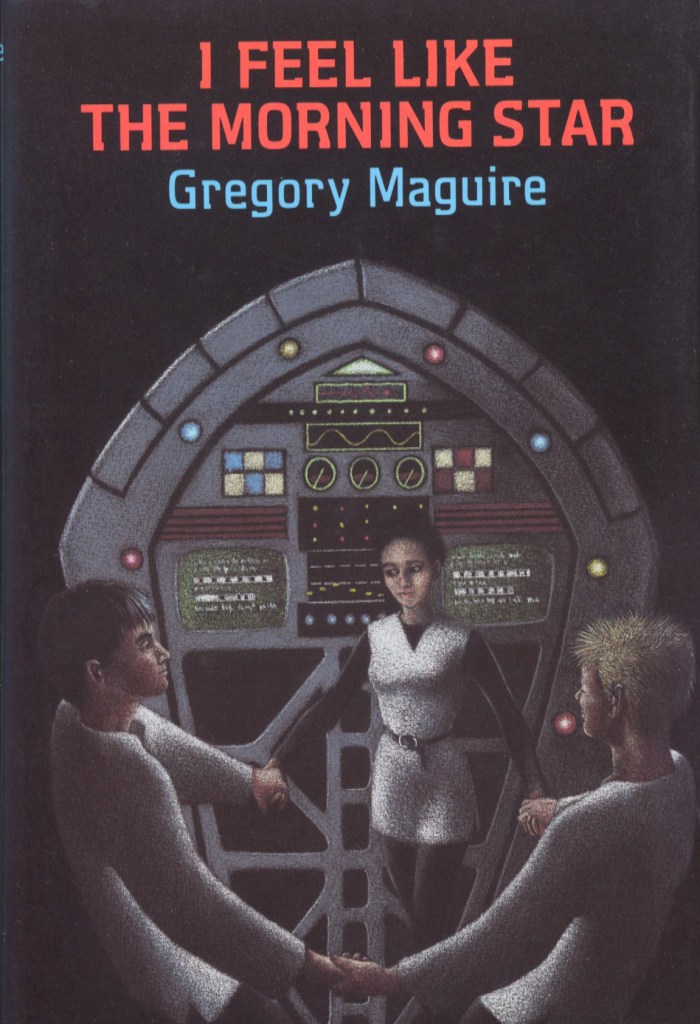

The sense of hope in Gregory Maguire’s I Feel Like the Morning Star radiates despite the dire circumstances the characters have been thrust into. At the cusp of a nuclear war, 1,000 people are chosen to evacuate into a habitat 4,000 feet below the Earth’s surface. Only 400 actually make it into the Pioneer Colony. Everything required for their survival is guaranteed, and a council of Elders maintains order. After five years in this claustrophobic, narrowly controlled environment, the three teenage protagonists question their entrapment and resolve to take action. Mart, Ella, and Sorb are vividly distinct personalities who love one another and ultimately combine their talents to usher in a new world order.

For writers and readers like me, who feel troubled by contemporary societal chaos, this book from decades ago can offer relief. I slept better after reading I Feel Like the Morning Star. Young people offer us hope. As with Mr. Maguire’s book, Wicked, its musical, and now the movie, the fictional misdeeds of those in power seem disturbingly familiar.

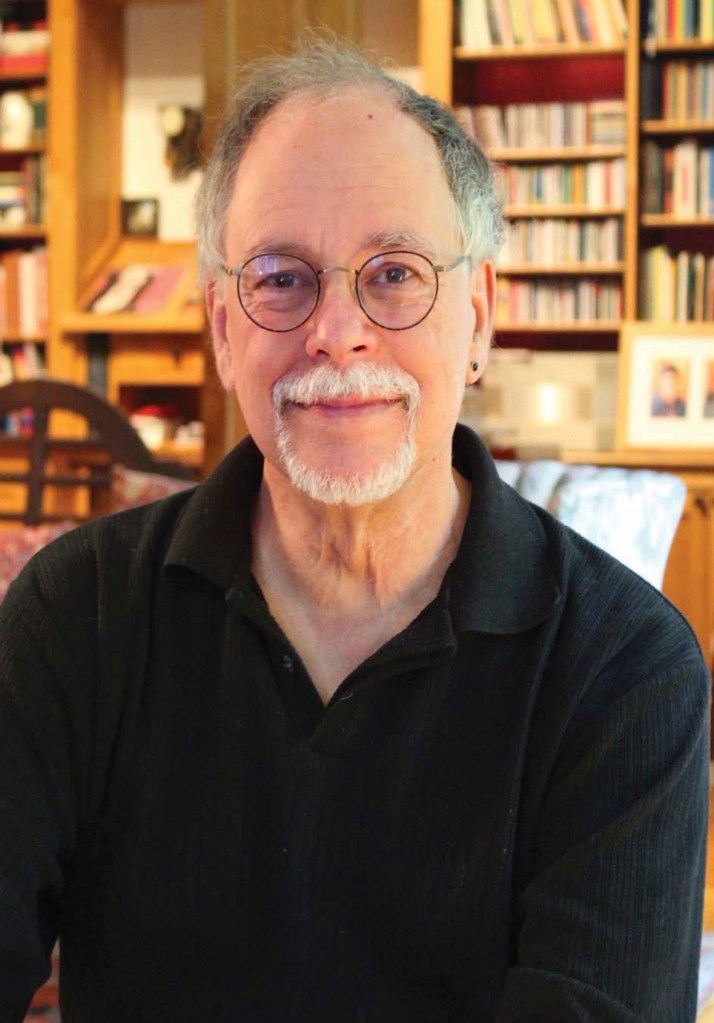

Gregory Maguire and I discuss his poetic and thoughtful approach to this post-apocalyptic story.

Interview

JAZ: Writers’ Rumpus readers are fortunate that you are willing to make room within your cornucopia of literary projects to share your thoughts with us, Gregory. Thank you for your altruism!

GM: You’re welcome—Glad to be joining you in this way!

JAZ: One might wonder why we should focus on this older book rather than Wicked or Elphie, which are more recent and marvelous escapes that are receiving abundant attention. They were written for an adult audience, though. What motivated you to direct I Feel Like the Morning Star toward young adults?

GM: At the time of writing I FEEL LIKE THE MORNING STAR, I had not yet written any novels for adults. That was not too far off, but I was still finding my way. I had not written a speculative fiction before, though in my thinking speculative fiction and fantasy are not all that different. One presumes a different future, one a different present. Οn an aside, at the end of 2005 I think it was, the New York Times declared that the work of literary fiction that had lasted longest on the bestseller list that year was Philip Roth’s THE PLOT AGAINST AMERICA—speculative fiction about a potential presidency of Charles Lindbergh. My novel, SON OF A WITCH, a fantasy set in Oz—and not relegated to genre fiction by the Times in that it was given a full-page review in the Sunday Book Review section—lasted on the bestseller list quite some weeks longer than the Roth. I am not saying it was a better book, but to accept an alternate history as “literary fiction” and an alternate present as “not” seemed specious. That’s beside the point of your question.

The truth is, in I FEEL LIKE THE MORNING STAR I was beginning to explore some of the themes that would come to a different kind of flowering in WICKED—some six years earlier. The three teen characters, not quite a love triangle, are struggling against an oppressive system that may in some ways have their survival at heart but also must keep them under control. There is also a magnificent black singer who only agrees to sing as a way to screen the young ones in their attempt to make a break. The place of music as political action, the need to work together to protect the weak, the requirements of courage—all of these are elements of WICKED, trotted out here in speculative fiction in a kind of experimental way for me.

JAZ: Originally, this book was simply science fiction set in the mid-21st century. Now it begins to seem like a battle plan and beacon of hope. In 1989, what drove you to write about this theme?

GM: I wish I could remember entirely! But I have always been interested in political action, especially as a person not driven with personal ambition to be front and center as a spokesperson or a leader. In the late 1980s there was a large push against the increasing use of nuclear power, and the fears for the health of the planet in the event of a nuclear conflagration either from war or from systemic breakdowns of the nuclear power industry. I remember going to a no-nukes rally in New York City, one of my first, and writing an op-ed about the experience for the Christian Science Monitor. I imagine the impulse to protest and to write a protest novel, as it were, are related.

JAZ: How does this scenario hold up for you now?

GM: You know, it’s funny. I originally conceived of I FEEL LIKE THE MORNING STAR as the first of three novels, but as it didn’t sell particularly well, I don’t think I ever even submitted the second nor wrote the third. (The second was called, in various iterations, MAZUS PIRATE or THE GUY AT THE TOP OF THE WORLD, and the third was going to be called SPLINTER CHASE.) They were to follow the story of the reclamation of liberty in a hobbled world after the Pioneer Colony had been evacuated and life was rediscovered not to have been as fully wiped out as feared.

Interestingly, one of the heroes of the third book was going to be a librarian in a very small rural community who, without pay or support from any municipality, kept the freedom to read alive, and was a single-handed guardian of liberty, not unlike the monks who “saved” civilization in the dark ages. As we face increasing censorship issues today, this seems to have been a prophetic thought, though I never wrote the novel.

JAZ: Perhaps I Feel Like the Morning Star didn’t sell as well as you would have liked because it was before its time. Interestingly, the paradigm for Pioneer Colony inhabitants is that they were chosen with a “fair distribution” of ages, sex, and racial origin. The concept of selecting who in our society would be given this survival option in the face of atomic war is daunting, and perhaps would not be as fair.

GM: It’s very natural and very high-school (unnatural!) at the same time, isn’t it? Not fair at all, and yet no one ever promised us in our cradle that life was going to be fair. I am less certain that I am right than I once was—one has to ask the question, How would I handle a Sophie’s Choice like that myself? Would I refuse to play entirely—and at what moral cost that?

JAZ: You handled the setup about the war with delicacy. The President is named, but only once, and there is no mention of the cause or origin of the atomic war. It is clear that Boston was decimated, but the residents of Pioneer Colony are unsure of the extent of the destruction to the rest of the world. It is enough to know that there was good reason for the survival colony. How did you determine how much to include of the war?

GM: One reason I haven’t written too much speculative fiction is that my grasp of both science and politics is fairly immature. I didn’t want to presume to write about the causes of the war because I would have to get into theories of rightness of behavior, and that would be distracting and also shift the novel’s close focus on adolescent character to the larger and (still) more mysterious behavior of powerful adults.

JAZ: Character begins with naming. Elphaba’s name in Wicked was a response to the initials of The Wizard of Oz’s author – LFB. Glenda and Belinda, the young twins in I Feel Like the Morning Star, seem like a tryout for the name Galinda/Glinda you would give six years later to the allegedly good witch in Wicked. Is there a story behind the character names in I Feel Like the Morning Star? Garner Jones? Sorb? Mazerius? Is Mazerius intended to represent a sacrificial lamb?

GM: What good questions, this is! Yes, I remember a little bit about characters. I had forgotten about Glenda and Belinda! (I haven’t read this book in nearly forty years!). I do remember a few things. I had a practice for the first ten years of my life of using the names of children’s book writers I admired as names in my books. So “Garner Jones” was certainly formed from the last names of Alan Garner and probably of Diana Wynne Jones. “Sorb” was a play on Zorba the Greek (Sorb is part Greek, and so am I; indeed I’m writing this from Athens). I also liked that “Sorb” is part of “absorb”, a word which implies receptivity and even empathy, which is part of Sorb’s tender nature. Mazerius I am less sure of, but I do remember having read a little in Persian mythology in those years, and being interested in the Mithraic cult that preceded Christianity and in some ways uses some of the symbol systems that Christianity coopted and repurposed. Beyond that I’m not sure. But the character of MAZUS PIRATE, mentioned above, certainly was a Jesus figure and was killed at the end of that unpublished novel. (Was he the singer’s son? I can’t even remember.) Incidentally, Ella was named for Ella Fitzgerald.

JAZ: Tension between the elders who remember the world above and conform mostly without question to the rule-based survival order, the teens who resist, along with children too young to have known the natural world, form one of the triads in this story. The other is the relationship between the three teens, Ella, Mart, and Sorb, who all love one another in various ways. What is the power of three?

GM: Three is both the stable unit and the unstable one, in my book. I have often wondered how people write plays with only two characters—I always think there must be a third, and perhaps invisible character (time?) who is adding the internal pressure to the binary code. Myself, I think thinking in binaries is possibly one of binds we have gotten into ever since the computer age began—any element has a value of either 0 or 1, with no variables. Losing the ability to tolerate variability is dangerous for our species. In a system of three, the variables are also shifting, which requires us to keep attentive—to keep processing—not to lock into inertia.

JAZ: The situation in this narrative is more dystopian than your revisionist fables, yet you wove this tale with music and a more poetic voice. The lovely seashell amulet Sorb gives to Ella is a talisman of the real world. The secret spinet piano that Mart makes available to Ella reflects her love of classical music. Mem Dora Prite’s voice. Yet the stresses of the situation prevent Ella and Mem Dora from expressing their music until they are committed to escaping. Was this in contrast to the weight of the problem?

GM: I remember one of the prompts for this novel was a dream I had about being in some sort of industrial warehouse, abandoned and dusty, and exploring it or trying to escape it, and coming across a spinet locked in a cage like a pig crated in a pen—Anchor fencing on five sides above the floor. To lock up music! I have played the piano in the past, and composed, and I woke from that dream with a sense of panic. Music as protest has always been powerful to me, and you may realize that I made sure Elphaba could sing, and sing beautifully, in the novel WICKED long before Broadway got a hold of her and made her a powerhouse belter.

JAZ: Sorb’s lyrically described dreams, those of Manila, where he had never been, somehow connected him with his mother’s memories, and the vivid dreams of the angel were pivotal. The angel dreams were so tactile, so vivid. These visions catalyzed his urge to “do” something. Why an angel?

GM: I think of Saint Paul in prison, and if I remember correctly Saint Paul was freed from his prison by angels. At any rate, in Old Testament stories angels are agents of comfort and sometimes conveyance. Sorb is also a sensualist (which in my lumpen proletariat way I am, too—but who isn’t?). Writing about the tactility of angels in Sorb’s largely adolescent emotional experiences allowed me to eroticize his reaction to the world without making the piece a total love story.

JAZ: Each day, the colonists take tea with Larmer. This seems similar to the laudanum used in the past to calm people, including children in orphanages. The brutal Lisopress treatment that Sorb endures reminds me of a scaled-down version of the One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest lobotomy procedure. Convincing ways to control a captive population. How did you determine the optimal amount for your young audience without going over?

GM: What is not said is always more scary than what is said, and so being suggestive rather than clinical both relieved me of having to follow medical reality and also helped me require the reader to build the tension in his or her own mind.

JAZ: An excellent point. You said online that you are taking a creative break from the writing you have been doing. One creative approach is to dig a hole deeper and deeper, while another is to dig new holes. What new holes are you exploring?

GM: I have two pots on the hob—one is a kind of exercise of memoir, and the second is my first attempt at a play. Both are “playing around” as it were, and like the sequels to I FEEL LIKE THE MORNING STAR, they may not ever see print. But they keep me engaged on a daily basis. This helps me continue to process the world of 2025 as it unfolds to my alarm and also within the reach of my hope.

JAZ: -Thank you for providing fellow writers and your readers with an exit hatch!

“Remember this: Nothing is written in the stars. Not these stars, nor any others. No one controls your destiny.”

― Gregory Maguire, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

What a great interview Joyce and Gregory. So informative, and well, hopeful for the writing process. I’ll have to find I Feel Like the Morning Star as it sounds fascinating, esp. perhaps in our times. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hi Kate. Good to hear from you. Yes, we are all needing hopeful ideas. This book shows how Gregory has explored the conundrums of power in a way appropriate for teens, who are our future.

LikeLike

We do need hope in the world. Thank you.

LikeLike

Adaela, yes, this is one significant role literature fills. Your thanks and mine for Gregory and his message.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading Gregory’s thoughtful responses to your excellent questions, Joyce. I Feel Like the Morning Star sounds fascinating, such a great premise. Thanks to both of you!

LikeLike

My pleasure, Marcia. Gregory has always been a thoughtful respondent giving readers much to consider. having this conversation with him was certainly fun.

LikeLike