“Impossible!” you cry. “Nonsense!” I reply. Here are ten common issues found in novel manuscripts and tips to help you avoid or correct them.

#1: Repetition Repetition Repetition

Too much repetition can annoy readers to the point that they abandon your amazing novel completely. But have no fear: the easiest to fix (and most commonly found) form of repetition is overuse of a single word. In Microsoft Word, which many writers use, you can seek, find, and switch any word you suspect you’ re repeating a bit too often. Frankly, it never hurts to check a few suspect words, as it only takes several quick keystrokes. Watch out: the more unusual the repeated word, the more your readers will recall it. But trust me, the commonly repeated and often uncalled for words like just and even will bother readers just as intensely, if not more!

A trickier type of repetition to detect is when phraseology repeats. Yes, it can help readers to follow your plot if you clarify or repeat key details, but watch out for using the same wording, especially if the repetition occurs in the same paragraph, page, or chapter. Figuring out how and when to clarify details is a challenge, but one that is truly worth putting our attention toward.

#2: Passive Language

If you want to put your readers to sleep, use a lot of passive language. (Remember your high school history books? It’s a miracle I still enjoy historical fiction so much after being subjected to such snooze-worthy textbooks in my youth.) If you want to keep readers engaged, avoid overuse of sentences constructed with is, are, was, or were, the hallmark of telling sentences. Yes, passive sentences have their place, but engage active verbs (such as scramble, jump, and dance) as much as possible to help you SHOW not TELL. For more about this subject, especially how to effectively TELL and then SHOW, check out my 2019 post Show and Tell for Writers featuring examples from picture books to YA novels.

#3: Words that Dilute Impact

Almost is my biggest pet peeve, as inserting it before a verb stalls action in its tracks. Go ahead, be brave. Let your main character trip, fumble, or mess up in spectacular fashion. Remind yourself that perfect characters are boring! Let yours get in trouble!

Just and even are other words that commonly sneak into our sentences without detection (refer back to Tip #1). Besides introducing repetition, these words dilute or delay impact: if they show up too much, they make readers want to pull out their hair! If you recognize you lean too heavily on any of these words, seek, find, and evaluate each one to make sure they’re necessary. I feel so strongly about the potential negative impact of these three culprits that each warranted its own post. Here are the links if you’d like to delve into their destructive capacity further:

Don’t Let ALMOST Sabotage Your Plot!!

JUST: Let it Stay or Hit Delete?

EVEN: JUST’S SNEAKY COUSIN

#4: Is that a Dialogue Tag?

As the word dialogue suggests, dialogue tags pertain to speech. The most common dialogue tag by far is said, though exclaimed, replied, and yelled are three examples that also work when used judiciously. If a character laughs, can that be a dialogue tag? Nope! If a character smiles or sighs? Nope again. In fact, while those words can help identify which character is talking, they describe actions, not speech (more on that distinction in the next tip). The big copyediting difference with action identification is that it calls for a period before the quotation starts instead of a comma. The good news is that if you identify a character with an action, you don’t need to add a dialogue tag. Here are two simple action examples that demonstrate action identification properly punctuated.

Juanita snorted. “You’re kidding me, right?”

Stephen sighed. “Okay, okay, I’ll mow the lawn before I head to the party.”

For detailed instruction on punctuating dialogue tags before, after, or in the middle of two-part dialogue, check out this aptly named post from September 2019: How to Punctuate Dialogue Tags.

#5: An Overabundance of Dialogue Tags … Or None at All

In middle grade and young adult novels, dialogue tags definitely have their place. But why do we use them? To identify who is speaking, which is especially helpful when two or more characters converse at length. An alternative to using dialogue tags is to identify characters through their actions or a physical description. In practice, it’s advisable to switch it up.

My examples in the previous tip were simple, but here’s a more impressive example from The Bletchley Riddle, an MG historical adventure novel by the brilliant team of Ruta Sepetys and Steve Sheinkin (page 87):

“Of course.” Colin adjusts his gray cap, revealing his tanned face. A spark of mischief glimmers in his eyes. “You up to some trouble, Lizzie?”

The opposite but related problem is talking heads, a conversation between characters without any dialogue tags or defining actions. Whenever I encounter this issue, I often need to read and re-read the given passage to determine which character is talking. By the third time through, I abandon the book and move onto another. Don’t let your hard-worked masterpieces fall into either trap!

#6: Putting the Cart Before the Horse

This issue refers to describing a response before the related action occurs. This also refers to using the wrong verb tense, which can make it seem as though something is finished and then miraculously starts up again. I recently read a book that had that issue, all because a character ate the last pastry and two paragraphs later, the family sat down to breakfast with a full tray. If the author wrote, “Our breakfast had consisted,” instead of “Our breakfast consisted,” the timing would have been clear. In fact, there are many more creative ways the timing issue could have been avoided.

When narrating in present tense, switching to past tense is how we can show an event occurred in the recent or distant past. A particular watch out with present tense is that you can’t reveal things that haven’t yet occurred. Characters may suspect something will happen, but they can’t know with certainty. When relating a pivotal past event, whether narration is in present or past tense, this could indicate flashback territory.

To learn more about flashbacks and how to use them, check out my February 2021 post, Flashbacks: A Trip Down Memory Lane.

#7: Tricky Inconsistencies

The best way to detect tricky inconsistencies is to read through our entire manuscripts and even better, enlist critique buddies to do a full review. Watch out for name changes, shifting physical descriptions, plot glitches, or anything else. I just edited and copyedited an 80,000 word Holocaust memoir and caught major plot discrepancies related to inconsistent descriptions of homes. I also detected (and fixed) different spellings for various names. In my own work-in-process, I was chagrined to realize that I had unintentionally switched a character’s name halfway through! If you have an inkling you may have switched a name or two (of a character, place, or object), the seek and find feature in Word can help you to root out the inconsistencies before your whole novel review.

#8: Fluctuating Tenses

Whether you choose to write your masterpiece in present or past tense, stick with it! Yes, as I mentioned in Tip #6, there are times when the plot calls for switching from present to past to recall something had occurred in the (you guessed it) past. But all too frequently, I see tenses switching back and forth without rhyme or reason. How can that be prevented, you wonder? First off, commit to which tense fits your writing style and your novel’s plot. If you’re unsure, this may subconsciously be the root of the problem. To help you determine which tense is best for each new manuscript, my suggestion is to write two versions of the first chapter, one in past and one in present. You may figure out which is best yourself, or you may need to enlist the opinions of your critique buddies. But once you make a decision, embrace it wholeheartedly. If you’re murky about recognizing the differences between present and past tense verbs, I recommend a little grammar review. Last but not least, when you review your own work, keep an eye out for unintentional changes in tense.

If you’re interested in a more in depth analysis about the pros and cons of each tense complete with examples from exceptional middle grade novels, check out this post from March 2022: Past or Present? Learn Which Tense is Best for Your Narration.

#9: Unnecessary Filter Words

This tip was covered extremely well by Joyce Audy Zarins in her enlightening December 2023 post entitled Editing tip: Ditch most filter words. In essence, these culprits are used to explain a character’s sensory experiences or thought processes. Common examples are see, feel, hear, think, and believe. These words sneak into in my writing, so if you relate, trust me, you aren’t alone. Becoming aware of this insidious issue is more than halfway to solving it!

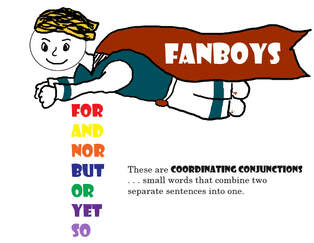

#10: The Dreaded Comma Splice

A comma splice occurs when two complete sentences are spliced together with nothing but a comma between them. There are two ways to fix this extremely common issue. The first is to use a comma plus a FANBOY (FOR, AND, NOR, BUT, OR, YET, SO). The second option is to replace the comma with a semicolon.

Incorrect: The children set up a roadside stand, friendly neighbors stopped for lemonade and cookies.

Correct: The children set up a roadside stand, and friendly neighbors stopped for lemonade and cookies.

Correct: The children set up a roadside stand; friendly neighbors stopped for lemonade and cookies.

How do you avoid comma splices in your work? Note that the incorrect example can be broken into two separate sentences. Once you identify that you could separate your larger sentence into two, remind yourself that you have not one but TWO ways to fix it!

I hope you feel empowered to try your own copy editing – a critical step before you submit your manuscripts to agents or editors.

How did I learn all these nitty-gritty details? I’m the product of a family who debated grammar at the dinner table and played endless (and extraordinarily competitive) rounds of Scrabble. Professionally, I earned an MBA from NYU and a MA English teacher’s license for grades 5-12. Since 1993, I’ve been tutoring students in creative and essay writing, reading comprehension, standardized test prep, and personal statements for college and grad school. I’m also a longtime member of SCBWI and the editor/copy editor of the Writers’ Rumpus blog as well of the WWII novel The Medic’s Wife: Love, War and Secrets by Edmund Krusynski. Additionally, I’ve edited/copy edited picture books, short stories, chapters, and full manuscripts for kidlit and adult authors, including the upcoming memoir of a Polish Holocaust survivor. If you’re interested in learning more about my offerings, check out my website, laurafcooper.com.

Excellent tips! Guilty on all…but I have been getting better at catching myself on some of these! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Angie, thank you for your comment. Kudos to you for being aware of some of these issues and catching yourself! We’re all guilty of some of these at least some of the time!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great tips, as always, Laura! I’m taking notes 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Hilary! I’m glad you found this helpful!

LikeLike

A perfect post for all writers. Thanks for sharing this, Laura!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cathy, my goal is to help writers achieve their dreams! Thank you for your comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post, Laura! Thanks for sharing your expertise!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Kim!

LikeLike

Marti and Marcia!

Thanks for commenting! I have to watch out for too many BUTs, as well as for overusing clever words that stick in my brain.

LikeLike

Great post, Laura. We can all use a refresher on grammar from time to time. Well, maybe not you .

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this GREAT post, Laura! These organized tips will be so helpful to review when polishing my work. I tend to use but and that a lot. Another one I search for is ly words, just in case I’ve overdone the adverbs (which I often do). 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people