Guest Post by Heather Preusser

Chances are you’re here because you read Vicky Fang’s fabulous introduction to writing chapter books. Vicky talked about the inspiration for her Ava Lin series and how she wanted to create “books that were captivating [her] kids and turning them into readers.” Her kids especially loved funny, relatable stories. I’m hoping to build on Vicky’s blog post, focusing specifically on humor: How do you create a humorous chapter book series that engages young readers and keeps them turning page after page after page?

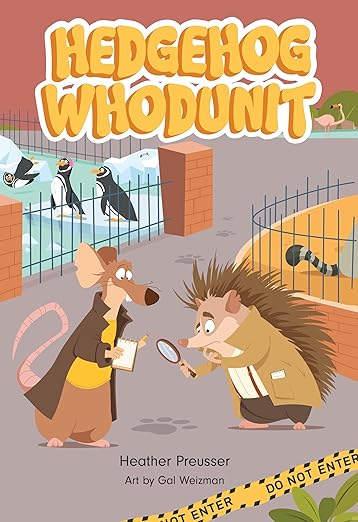

Full disclaimer: I don’t consider myself a funny person. When I wrote my HEDGEHOG WHODUNIT series about a sleepy hedgehog detective and his tireless rodent sidekick solving animal antics at City Zoo, I didn’t set out to write a funny chapter book. I set out to write a book I found entertaining. I worked on one round of revision during the pandemic, and I simply wanted to escape into a punny mystery where the characters issued flea bargains instead of plea bargains and sub sandwiches instead of subpoenas. I wanted to laugh. “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader” is a writerly proverb often attributed to Robert Frost, and the same is true for laughter. The writer’s enjoyment during the writing process will translate onto the page for the reader. So that’s my first piece of advice: Write a book you enjoy.

Because a write-a-book-you-enjoy approach may not be helpful for everyone, the teacher in me did what I always do in the classroom: I backwards-designed this blog post. I took a back-door approach to comedy, drawing on John Vorhaus’s THE COMIC TOOLBOX: HOW TO BE FUNNY EVEN IF YOU’RE NOT. I was interested in what Vorhaus had to say. How much of his advice was intuitive, and how much can we apply to chapter book writing? A lot, it turns out.

The Comic Premise

According to Vorhaus, any time you have a character that looks at the world from a particular perspective, you have a gap between the character’s reality and their comic reality. Comedy lives in that gap. To create the comic reality for your chapter book idea, look for something unexpected. For example, in HEDGEHOG WHODUNIT, Hitch’s “real” reality is that he’s a hardboiled hedgehog detective who keeps the zoo safe by putting culprits behind bars, but his comic reality, the unexpected irony, is that in book one, he’s looking for a giant panda bear. I was amused by the idea of a missing mammoth mammal, and I thought young readers would be as well. Then illustrator extraordinaire Gal Weizman added to the amusement by hiding the panda in the background!

The gap between Hitch and Vinnie’s personalities—and even between their own individual characteristics physically and cognitively—is also part of the comic premise of the series. Vorhaus refers to this as “The Law of Comic Opposites.” Hitch’s character came to me almost fully formed. I knew I wanted him to be a slow-moving hedgehog (okay, originally he was a sloth, but I talked about that in another post), so I made him quick-witted. And I knew Vinnie, Hitch’s sidekick, needed to be the opposite. He needed to be quick on his feet, so I went with a rat. I also loved the play on words since, as the informer, he’s often ratting on the other zoo animals. I also made sure Vinnie wasn’t the sharpest tool in the shed (not that tools or sheds are involved), creating more gaps—more room for comedy—between what the young reader knows and what Vinnie knows, which, it turns out, is not a lot. Hitch and Vinnie are an odd couple of sorts, a forced union that must work together to solve each case.

Comic Characters and The Comic Perspective

Vorhaus describes the comic perspective as a character’s unique way of looking at the world, which—of course—is at odds with the “normal” world view; it’s a character’s own individual comic premise. And again, the greater the gap, the greater the laughs, so Vorhaus encourages writers to use exaggeration to take a character’s comic perspective “to the end of the line.” Hitch loves sleeping and loathes anything that has to do with work or Vinnie, especially working with Vinnie. As part of his comic perspective, Hitch also states the obvious—usually by pointing out Vinnie’s cluelessness. It turns out Vorhaus has a name for this as well: “Telling the Truth to Comic Effect.”

Vinnie, on the other paw, is like one of those exhausting windup toys going nowhere that kids always leave behind at the zoo. This is echoed in how he talks as well. Whereas Hitch speaks in short, simple, to-the-point sentences, Vinnie often uses long runaway sentences that have a bit of breathlessness to them. Because Vinnie is a scraggly, wire-haired rodent who chews on his own greasy pink tail (gross!), I wanted to add an unexpected detail, so I made him a food connoisseur as well. He’s constantly daydreaming about food, talking about food, cooking food and eating food—and sometimes he’s eating the clues as well, which leads us to…

Character Flaws

Flaws are failings or negative qualities within a character. They reflect who a character really is and are often at odds with that character’s self-image (more gaps, more comedy!). Flaws also create emotional distance between a character and the audience, making it safe for readers to laugh. Ideally, some flaws will complement the comic perspective while others will find conflict with it. Let’s take Hitch, for example. He’s a reluctant detective at best, which is aided by his lazy, anti-social ways, but his clever wit as well as observant nature hinder his “I’d rather be sleeping” mentality.

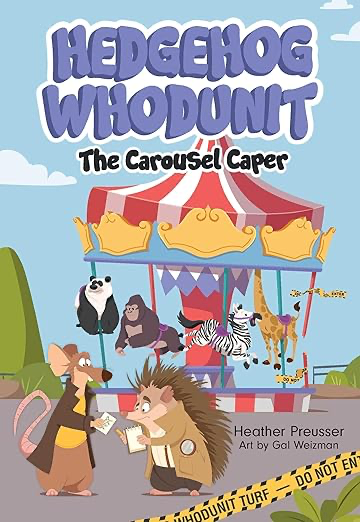

Vinnie’s tirelessness is aided by his eagerness and distractibility. That he doesn’t have a moral fiber in that scruffy, scrappy body of his also probably helps, but his ignorance sometimes slows him down, like in book two, THE CAROUSEL CAPER, when he creates a “safe house” in the least safe place in the zoo: a construction site.

Humanity

For the audience to care, Vorhaus recommends writers tap into a character’s humanity, building a bridge between the character and the reader. Sure, Hitch is sedentary, introverted, and snarky, but when push comes to shove, he’ll do the right thing: He’ll take the case because he wants to keep the peace. Hitch says he’s prickly—after all, he has 6,000 spines covering his back—but underneath those spines, he’s all hedgeheart. In book two, he’s even huggable!

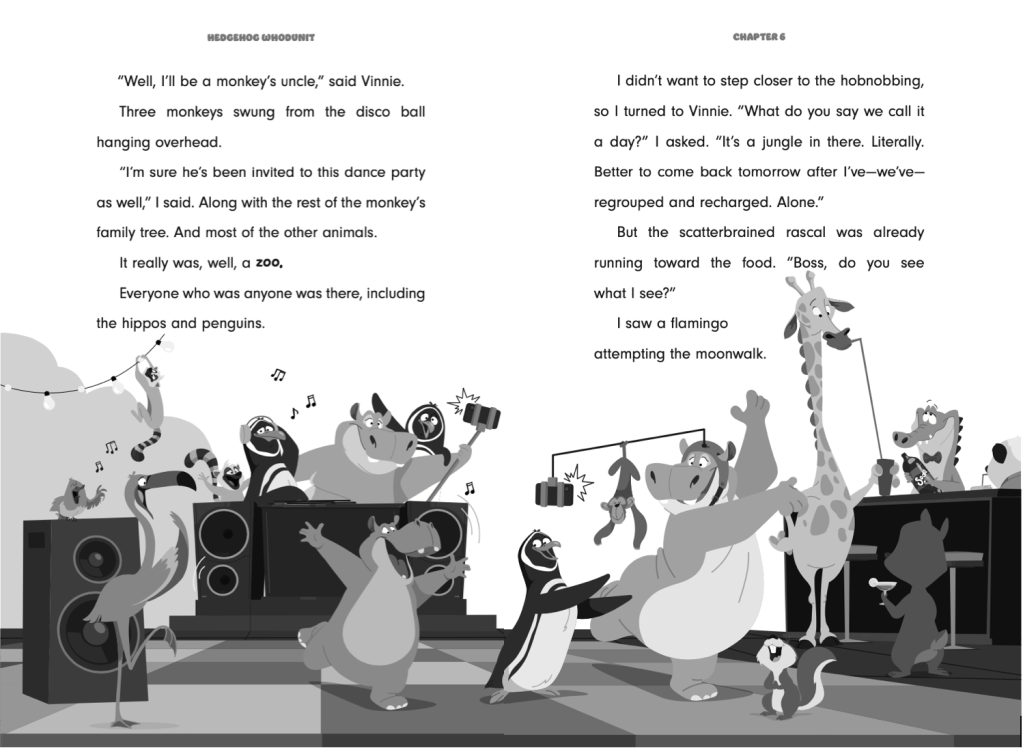

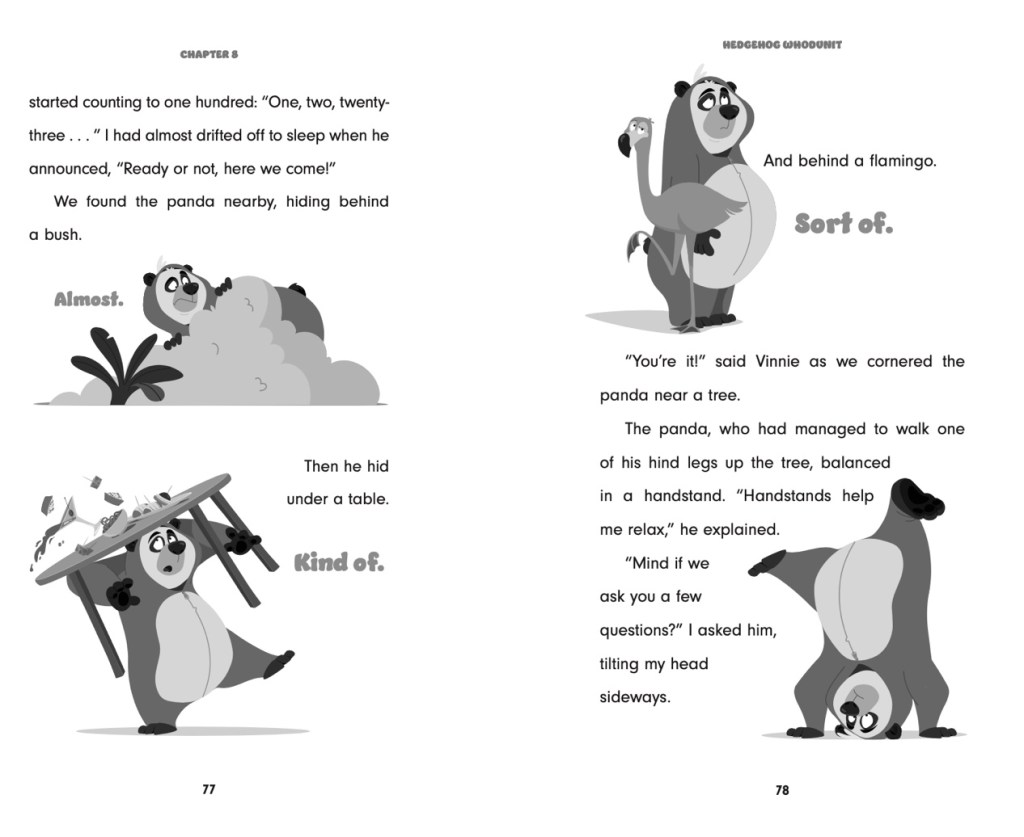

Additional Tools: The Wildly Inappropriate Response

Vorhaus discusses a lot of other helpful tools you can add to your comedy toolbox. I want to highlight one more that I find especially useful when writing chapter books: “The Wildly Inappropriate Response.” Notice I said “find” (present tense) instead of “found” (past tense) because I wasn’t consciously aware of this tool while I was writing; I just knew that I was having fun, and that’s because “The Wildly Inappropriate Response” goes hand in hand with exaggeration. Vorhaus describes it this way: “Just pick a situation and ask yourself what the logical response to that situation would be. Then find the opposite of that response.” Turns out that’s exactly what I did—with the help of my astute critique partners and my insightful editor, Erinn Pascal. In earlier drafts, when Hitch and Vinnie came across the missing giant panda at a disco party at Lemur Lounge, they just let him go. There was no confrontation. During the revision process, I started to play. And have fun. And I inserted a wildly inappropriate response: a hide-and-seek scene that had me laughing out loud while I wrote at my local coffee shop. Then Gal brought Hitch’s world to life. She created hilarious illustrations of a ridiculously adorable giant panda trying to hide behind a bush (almost), under a table (kind of), and behind a flamingo (sort of), and it became my favorite scene in the book.

The same is true for book two: When Vinnie finally confronts the prime suspects, what does he do? Challenge them to a cabbage-eating contest, of course! Spoiler alert: Vinnie wins.

So the next time you’re trying to add humor to your writing and you’re stuck, turn to Vorhaus’s suggestions: add gaps (between realities, between characters, between the characters and the reader) while also building bridges to ensure the reader cares. Throw in exaggeration, a game of hide and seek, a cabbage-eating-contest, or a scene that makes you chortle in the coffee shop while writing it because, chances are, if you find it entertaining, young readers will as well.

About Heather Preusser

Growing up in Maine, Heather Preusser read all the Nancy Drew mysteries. Every. Single. One. Now she writes her own mysteries featuring a hardboiled hedgehog detective and his tireless rodent sidekick solving animal antics at City Zoo. HEDGEHOG WHODUNIT, the first book in her chapter book series, released in October 2024. The second book, THE CAROUSEL CAPER, came out in July 2025, and the third book, THE PROTECTIVE ORDER OF PEANUTS (P.O.O.P.) will be available in 2026. She is also the author of the picture book A SYMPHONY OF COWBELLS (Sleeping Bear Press, 2017). When she’s not writing or teaching high school English, Heather plays with her six-year-old, a budding boxitect. She and her family live in Colorado. You can learn more at heatherpreusser.com.

Well done tips, Heather!

LikeLike

Great post!

LikeLike

Excellent post. Thanks.

LikeLike

This was great! Thank you, Heather!

LikeLike

Interesting, helpful, and funny! Thank you, Heather!

LikeLike

Heather, this post is so entertaining and helpful! Thank you for guest posting with us!

LikeLike